Every day in English Tourism Week, we are sharing one of our ‘Top Ten Tourist Treats’ here at Bradford Cathedral.

Today’s treat is our Significant Memorials

There are a number of significant memorials and plaques on the walls of Bradford Cathedral but we’ve chosen to highlight two men (yes, two!) who have craters on the moon named after them, and two medical pioneers!

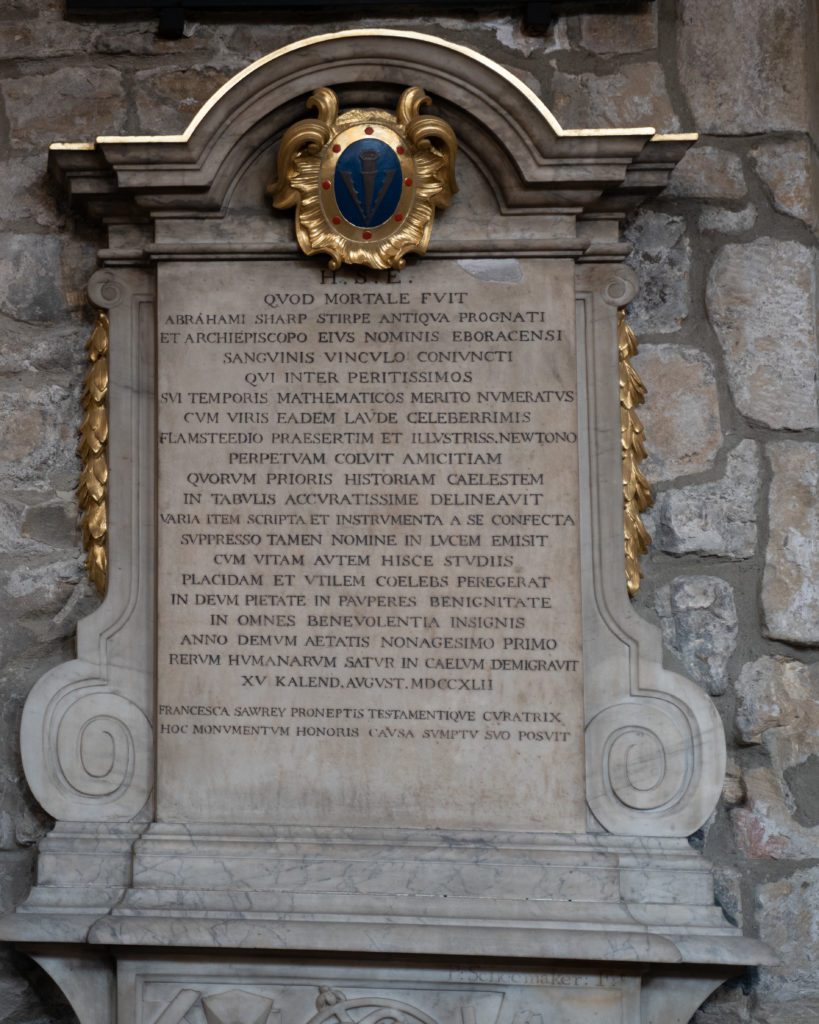

Abraham Sharp memorial – World-renowned mathematician and astronomer

Abraham Sharp (1653 – 1742) was buried in Bradford Cathedral and his memorial is on the wall of the north aisle. Look for the memorial made of marble, with gold flourishes, a Latin inscription and carvings of mathematical and astronomical instruments at the bottom.

Born in 1653, he was the son of a wealthy wool merchant, who grew up at Horton Hall and attended the local village school and then Bradford Grammar School, which was located at that time in a building very close to the Cathedral. Whilst there, he developed a love of mathematics.

He eventually ended up in London as assistant to the first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, and also moved in the same circles as Sir Isaac Newton (whose name is mentioned on the memorial) and Edmond Halley. In 1689 Flamsteed engaged Abraham Sharp to make his famous mural arc with which most of the observations for Flamsteed’s “Historia Coelestis” (Catalogue of fixed stars) were made.

In 1693, he returned to Little Horton, inherited Horton Hall and for almost forty years led a busy and contented life largely left to his own devices, although he was well known for his generosity towards others. The Hall had a central tower with a parapet, where Sharp set up a telescope that he had made himself. His account books show that he turned out an enormous number of instruments—sun dials, armillary spheres, micrometers, quadrants and sextants, lathes for turning ovals and roses, watchmaker’s tools, telescopes, for which he ground and figured the lenses—not only for himself, but also as orders. He even created a “way-wiser” to attach to a coach to measure mileages up to a hundred miles and made a telescope cleverly fitted into a walking stick.

He came from a nonconformist family and attended the Presbyterian chapel from the time it was established, near his home. He retained his pew in Bradford Parish Church (now Bradford Cathedral) and was buried here.

The Sharp Crater, a large depression in the Moon’s surface is named in his honour.

His memorial was designed by Peter Scheemakers, or Pieter Scheemaeckers II or the Younger, (1691– 1781) a Flemish sculptor who worked for most of his life in London. His public and church sculptures had an important influence on the development of modern sculpture in England. He is perhaps best known for executing the William Kent-designed memorial to William Shakespeare which was erected in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey in 1740.

Blue Plaque to William Scoresby Jr, 1789-1857- North Porch entrance

Emplaced by the Rotary Club of Bradford, 1996

Whaling Ship Captain, Arctic Explorer, Renowned Scientist, Social Reformer and Vicar of Bradford Parish Church, 1839-1847

William Scoresby Junior was born in 1789 near Cropton, Whitby, and made his first sea trip with his father, a whaling captain, around the age of 10, initially as a stowaway. He later became his father’s apprentice aboard the whaling ship and his father’s chief officer at the age of 17. They made many Arctic voyages together, including when they succeeded in reaching the highest northern latitude attained in the eastern hemisphere.

Upon his father’s retirement he was given command of a whaling ship at the age of 21 and he was a successful whaler for around 30 years. During his time in the Arctic, he undertook studies of the flora and fauna and documented the ice and snowflake formations under different weather conditions. His invention of a “marine diver” in 1817 enabled him to measure temperature, density and the marine life at different depths of the Arctic waters. On voyages between 1815 and 1822 he made observations and experiments with improvements to the magnetic compass and in an exhibition of the British Association in 1836 he showed the compass needle of his own invention, which was later taken into use by the Admiralty.

He made a detailed study of refraction in the Arctic and the North Sea as well as surveying and mapping the east coast of Greenland. In his voyage of 1822, he surveyed and charted 400 miles of the east coast, contributing significant geographic knowledge of East Greenland. He named Scoresby Sound, one of the largest fjord systems in the world, after his father.

He gathered his work together in the two-volume “Account of the Arctic Regions”, a highly significant work that marks the beginnings of the scientific studies of these regions. After publication of his journal of a Voyage to the Northern Whale Fishery, including Researches and Discoveries on the Eastern Coast of Greenland (1823) he was elected as a fellow of the Royal Society and his work brought him into contact with many of the leading scientists of his day, including Faraday, Joule and Ampere.

Scoresby published over 100 works in his lifetime and even after entering the Church, he continued with his scientific studies. In 1831 he was a founding member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

In 1839 he became Vicar of Bradford, and he said: “the immense labour of this parish of 132,000 souls requires all my time, so that I can do but little in science”. However, he did continue with his scientific studies and experiments, both nationally, internationally and locally.

He was shocked by the conditions he found in Bradford and set up a ‘Sanitary Committee’ which inspected and logged crowded slums and basement dwellings. He recorded the pollution in the canal, with its dye-stained water and foul gases. He was an opponent of child labour and noted the conditions of young factory workers and their lack of education. In his 7 years in Bradford, he did so much to improve the living and working conditions and the education of children and adults in Bradford. From his national and international lecturing, he raised the money to endow a network of schools in the town. Over 6,000 children received an education at the day and Sunday church schools that he set up.

His leadership style wasn’t welcomed by all. He clashed with factory owners, understandably, but also with local Anglican clergy, including Patrick Bronte, non-conformists and philanthropists.

Scoresby continued with his scientific interests whilst in Bradford: in 1845 he could sometimes be found in the vicarage conducting electro-magnetic experiments with a young JP Joule. They published their results in 1846, proving beyond doubt that the electric motor was not in perpetual motion and putting an end to the “electrical euphoria” that had swept through Europe and the United States for the last decade. Scoresby was the owner of a massive magneto machine, on which they conducted their experiments. It had enormous magnets, capable of producing a very large current. He was received by Prince Albert and showed him some of his magnetic experiments on his magneto machine.

Scoresby’s health was ruined by his time in Bradford and he tendered his resignation twice, including in 1844. The Bishop of Ripon offered him a sabbatical and he went off giving lectures in America and Canada, among other places. He finally resigned in 1846, saying: “The Lord sent me here for a great though painful work.” He left early in 1847 after being quite ill, without a church to go to.

However, in later years he undertook a voyage to Australia to test the effect of iron ships on the compass and to adjust it, and he became an active member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. His papers, log books, detailed drawings, magnetic instruments and botanical and geological specimens are in Whitby Museum.

There is a crater on the moon named after Scoresby. It is a lunar impact crater in the northern part of the moon’s near side. Scoresby was an Arctic explorer who set a record for the furthest voyage north and the lunar crater is also far north on the moon.

Turner/Whyte Watson Chemotherapy plaque- North Transept

The plaque is a memorial to these two men and their pioneering work and significant achievements in the field of chemotherapy. Professor Turner (1923-1990) was a British scientist known for his pioneering work in cancer research and chemotherapy. He led a team at Bradford Royal Infirmary developing key parts of chemotherapy treatment, now a routine step for millions of people diagnosed with cancer. Whyte-Watson (1908- 1974) is perhaps best known for his pioneering work in collaboration with his colleague Professor Turner, in the treatment of breast cancer after their researches in the use of chemotherapy. He was instrumental in getting self-examination included as part of the procedure for detecting breast cancer.