Textiles

Bradford Cathedral is home to many wonderful textiles. Here is some information on a selection of them.

Good Shepherd altar frontal, designed by Ernest Sichel

This altar frontal, with the central figure of Jesus, the Good Shepherd, was designed by the Bradford artist Ernest Sichel (1862-1941) and was embroidered by members of the Ladies Diocesan Embroidery Association, for the high altar of the old Chancel, which existed before the extensions to the east end of the Cathedral in the late 1950s.

After the extensions, the altar frontal was placed in the new St. Aidan’s Chapel but it has not been on regular display in the Cathedral for a number of years.

There is a long history of involvement in ecclesiastical embroidery in the diocese and there is still a thriving Stitching@Bradford Cathedral group today, which is open to all. In 2020, after over three years’ work, the group completed a series of kneelers to go around the high altar based on patterns by designer Polly Meynell; and their current project is stitching kneelers to go in St. Aidan’s Chapel, based on designs inspired by the current fabrics in the space.

Ernest Sichel was born in Bradford, of German Jewish descent. His father, who came from Frankfurt-am-Main, was the manager of the yarn and stuff merchants, Reiss Bros. in Currer Street and his mother was the daughter of Henry Foster, one of the founders of S & H Foster Ltd, Spinners & Manufacturers.

He was a painter, sculptor and silversmith, as well as a pastellist. In later life he spent a lot of his time as a portrait painter, as well as designing ecclesiastical embroidery and bronze work.

Sichel attended Bradford Grammar School, where he was a friend and contemporary of Frederick Delius. He studied at Slade School of Art and became friends with the artist William Strang. He exhibited his work at the Royal Academy, the New English Art Club, the New Gallery and the Walker Art gallery in Liverpool.

He returned to Bradford in 1890 and worked here for the rest of his life, creating work for institutions in the city, including Bradford Cathedral- for which he designed the Good Shepherd altar frontal and the bronze St. George on the World War One Memorial at the back of the Cathedral, near the refreshment hatch.

Louisa Pesel and the Khaki Altar Cloth

Louisa Pesel was born in Bradford in 1870, the eldest of five daughters of a merchant who later became a stockbroker. She was educated at Bradford Girls’ Grammar School and went on to study Design at what is now the Royal College of Art in London. Louisa studied Design under Lewis Foreman Day, a decorative artist, industrial designer and a significant figure in the Arts and Crafts Movement.

During the First World War Louisa worked with Belgian refugees in Bradford and she was also a founding member of the Bradford Khaki Club for injured and shell-shocked soldiers, pioneering the teaching of embroidery as occupational therapy.

This altar frontal, known as the Khaki Altar Cloth, is an example of the type of work that Louisa Pesel was engaged in with the soldiers as part of their rehabilitation. The soldiers worked to her design in cross stitch on linen and under her supervision.

The beautiful floral design is inspired by her time spent in Greece and the surrounding area and her study of Greek Island patterns, themselves inspired by the colours and flowers of the natural landscape.

The altar frontal was originally made for the chapel at the Abram Peel Hospital in Bradford, before being given to Bradford Cathedral. It is now part of Bradford Cathedral’s textile collection and was on loan to Two Temple Place in London for their “Unbound: Visionary Women Collecting Textiles” exhibition in 2020. Today it hangs in the Chapter House of the Cathedral and can be viewed by appointment.

Louisa Pesel’s life was unconventional for a woman of that time. She travelled widely and taught at the Royal Hellenic School of Needlework and Lace in Athens from 1903 to 1907. She became interested in Archaeology whilst in Greece and subsequently visited Egypt and Turkey, whilst also travelling to India to visit relatives. On her travels she collected fabrics and embroidery. She later wrote several books about the techniques she had learned and the history and symbolism of the embroideries she had come across.

After returning to England in 1908 she became a member of the Guild of Embroiderers and from 1910 she was commissioned to produce pieces and to give lectures by the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Louisa Pesel has recently come to prominence again, this time in the literary world, where she appears as a character in the novel by Tracy Chevalier, called “A Single Thread”.

William Morris and Co. Altar Frontal

Bradford Cathedral has a beautiful, intricate Morris and Co. altar frontal. This precious object had been forgotten about for many years until it was re-discovered in 2005. The Cathedral’s Head Verger at the time, recalled that some months after he joined the Cathedral in 2005, he was exploring the linen press in the Sacristy when he came across the altar frontal pushed to the back of one of the large drawers. Nobody connected with the Cathedral could remember ever seeing it before.

The V & A confirmed that it was a Morris design, although the original had strawberries rather than the pomegranates seen in this design. In Christian iconography pomegranates bursting open symbolise the fullness of Jesus’ suffering and resurrection.

It was in a poor state so could not be used. Its restoration was eventually triggered by the Cathedral’s wish to restore a World War 1 frontal (the Khaki Altar Cloth) for the Battle of the Somme centenary commemoration. Jacqui Hyman was commissioned to restore the World War 1 altar frontal and subsequently, the William Morris frontal.

The altar frontal is blue silk with an all-over embroidered design of pomegranates within swirling leaves. The design is listed in the 1912 embroidery catalogue of Morris designs. The superfrontal is blue silk with embroidered gold inscription and small embroidered pomegranates at either end. Both items are trimmed with matching green and blue silk fringing.

We don’t have an exact date but, comparing it with other Morris embroideries of similar design, it is likely to date from the 1880s.

Bradford had several William Morris connections and the Cathedral also contains early examples of stained glass windows by Morris & Co. After restoration in 2016, the altar frontal was fittingly placed in the Lady Chapel, underneath the Morris and Co. windows, for all to enjoy.

Khartoum Altar Frontal

by the Leek Embroidery Society

The Khartoum altar frontal has an interesting history. It was embroidered by 28 female embroiderers from the prestigious Leek Embroidery Society, in 1905, with the purpose of being taken to Khartoum to be placed in a church there in memory of General Charles Gordon, who died in Khartoum in 1885. The first Episcopal (Anglican) Cathedral in Khartoum, All Saints Cathedral, was opened in 1912, and one of its side chapels was dedicated to the memory of General Gordon, which was where the altar frontal was designed for and was then located.

It was brought to Bradford Cathedral from Khartoum in the late 1980s, via our diocesan links with Sudan. It wasn’t in a very good state when it came to us- with time, the tropical climate and a lack of care in later years all having unfortunately taken their toll- and the fabric of the altar frontal was and still is very fragile in places, with the gold thread also disintegrating due to the rotting of the inner silk core. In 2015 Jacqui Hyman, a textile conservator who was working with Bradford Cathedral at the time on the restoration and conservation of the WW1 and Morris & Co, altar frontals, took the Khartoum frontal and superfrontal, restored them as much as she was able to in her free time and for her own pleasure, and displayed them at exhibitions in subsequent years. Jacqui later gave the altar frontal back to the Cathedral.

Leek Embroidery Society

The Leek Embroidery Society was founded in 1879, inspired mainly by Mrs. Elizabeth Wardle, wife of Thomas Wardle, a well-known silk dyer from Leek in Staffordshire, who collaborated with William Morris on a number of occasions. The Society produced many altar frontals and other pieces of church embroidery in silk, along with secular embroideries. Many of their altar frontals are still in use today.The Society created work for the leading artists and architects of the day: Walter Crane, Norman Shaw, John Sedding and George Gilbert Scott.

Design of the Altar frontal

Richard Norman Shaw was a British architect who worked from the 1870s to the 1900s. He is considered to be among the greatest of British architects. As well as being primarily known for his country houses and commercial buildings, he also pursued work in the area of ecclesiastical textiles, particularly altar frontals. The design of the altar frontal features the architect Norman Shaw’s distinctive cross applied to a richly embroidered ground cloth.

Due to the fragility of the altar frontal it isn’t possible for it to be used for services or to have it out on regular display.

A viewing of the altar frontal is now possible on one of our ecclesiastical textiles’ tours.

Polly Meynell Textiles

In 2013 Bradford Cathedral celebrated the 50th Anniversary of Edward Maufe’s extension which marked its elevation from parish church to the Cathedral Church of St Peter, Bradford.

The Cathedral Chapter wanted to have a visible and vibrant marking of this chapter of the building’s life and Polly Meynell was asked to produce a set of textiles which would both reflect and celebrate Bradford’s rich heritage and seek to offer something of that back to God in worship.

Several visits to Bradford and two significant images (a map from 1889 and a modern landscape photograph) provided her inspiration and the materials for the project were sourced from the local area, mirroring the way in which different cultures live alongside each other in the City today.

The project provided four altar frontals, together with matching pulpit falls and stoles. There are also three gold coloured copes, displaying elements taken from the main designs. The final elements are the kneelers surrounding the high altar.

The altar frontals are the largest pieces and were designed first; the other pieces all draw inspiration from these.

Green altar frontal.

The green frontal is entitled “Journey”; it tells the story of our journey from darkness to light, from desolation to salvation. Both cityscape and rolling hillsides can be seen: we move through highs and lows before we reach a glorious, bright conclusion.

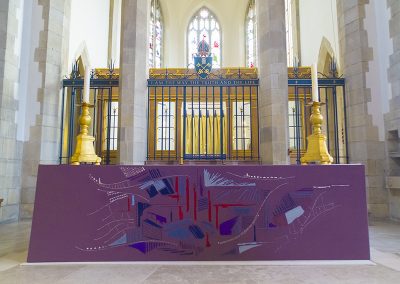

Purple altar frontal.

The purple frontal is entitled “Hope”. Purple is the colour of penitence and preparation. As we weave around a dense cityscape, at the centre we find hope in the shape of the broken cross. The presence of God in this place and the activity of the Holy Spirit are shown by the lines of silver thread weaving in and out of the City.

Red altar frontal.

The red frontal announces “Transformation”, when change occurs through the activity and grace of God. The design captures the moment with energy and power, though the pain and suffering are also present. It develops from darkness, divided and rigid, to become delicate, radiant and alive as it rises gradually to the top of the altar

The kneelers are wool on canvas and reflect all four of the church’s seasons at once and were to be completed as a community project. The Friends of Bradford Cathedral formed a group to complete the kneelers. Beginning in January 2016, a core group of about twenty people (supplemented by some eighty others) has put in thousands of hours of work.

We hope that what you see provides work which both reflects and celebrates Bradford’s rich heritage and seeks to offer something of that back to God in worship. We hope too, that the work demonstrates that Bradford Cathedral can hold twenty-first century craftsmanship within an ancient context, reflecting our place in this twenty-first century world.

About Polly Meynell

Polly Meynell lives in West Sussex and makes bespoke textile art works for individuals, public buildings, and sacred spaces.

She has a created large scale banners, wall hangings and panels in addition to bespoke robes and costume for special events, theatre and public buildings. She has designed for red carpet actors, theatrical productions, Bishops and Cathedrals, the Drapers’ Company and the Lutheran Church in New York USA, to name a few.

The Textile Industry in Bradford

The following information has been provided by Bradford District Museums & Galleries

Bradford was once Britain’s fastest growing industrial city. Over the first half of the 19th century, Bradford was transformed from a small market town into the woollen textile capital of the world. A beautiful green dale became a landscape dominated by huge mills and smoking chimneys. Bradford was nicknamed ‘Worstedopolis’ because the district grew rich making ‘worsted’, a fine wool fabric used in top quality clothing.

The story of Bradford’s textile industry begins in the Middle Ages when Bradford began to hold a weekly market where people could buy and sell cloth. Each week raw wool was bought at the market and carried back to farms and cottages across the district. Whole families would card (straighten and separate the fibres), spin and weave the wool by hand into cloth. This cloth would then be taken back to market and sold for a profit.

During the first half of the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution transformed this cottage industry into big business. A surge of new inventions meant that it was suddenly possible to do the work of carding, spinning and weaving with machines. This made the process of making cloth faster and cheaper. But the machinery was large and needed to be housed in mills.

The earliest textile mills were adapted from water-powered corn mills. When textiles became industrialised and steam power took over from water mills, these sites became the first factories, but they were still called mills.

Thousands of people flocked to Bradford to find work in the textile mills and Bradford became one of the most important industrial cities in the world with trade links that reached around the globe.

Bradford’s population rose from just 13,000 people in 1800 to over 103,000 by 1850. This enormous increase was caused mainly by people moving into the town to work in the new textile mills. Cheaply built housing for these mill workers was cramped and sanitary conditions were often appalling. The situation was so awful that in 1840 the average life expectancy was a mere 18 years of age.

Many millworkers were children and their treatment was compared to the slave trade. However with the introduction of acts such as the 1833 Factory Act (which reduced the working day to 9 hours for children under 12) the situation steadily improved. The city continued to grow. By the beginning of the 20th century Bradford supported over 350 mills and a large population of 288,000 with communities of immigrant workers from across England, Ireland and Europe.

In the 20th century, Bradford continued to produce textiles in huge quantities but the industry was in decline due to changes in fashion and foreign competition. During the 1970s the mills were reportedly closing at the rate of one per week. Many machines were sold off cheaply overseas to countries such as Egypt, India and Thailand. Between 1978 and 1981, 16,000 textile and engineering employees were made redundant in Bradford. By the 1980s, a city once famous for dealing with 90% of the world’s wool trade faced unemployment on a massive scale.

Today, computer technology and communications have led to another revolution in the workplace. Manufacturing industries have been replaced by service industries. Old mill buildings found new life as housing, museums and galleries and the base for digital and electronic industries.