The Building and its History

For many centuries, the building now known as Bradford Cathedral, and formally Bradford Parish Church, has stood on the hillside above the “broad ford” that gave Bradford its name. The site itself has been a place of Christian worship for nearly 1400 years, with the current church believed to be the third church in this location.

Christianity Comes to Bradford

It is likely that Christianity reached this site as a result of Bishop Paulinus’s mission from the court of King Edwin of Northumbria, between 627-633. Paulinus visited Dewsbury, where a Christian community was established, and from there a mission was sent out to Bradford-Dale. In early times, the parish of Bradford belonged to the Saxon parish of Dewsbury. It is believed that at some time a small wooden or wattle church would have been erected, with a preaching cross outside.

Two fragments of carved stone crosses, dating from Anglo-Saxon times, were excavated during rebuilding work in the nineteenth century. These fragments were re-sited and can be seen today in the walls of the North Ambulatory.

Norman Patronage

When the Domesday Book was compiled in 1086, the entry for Bradford read, “Ilbert hath it. It is waste”. At the time of the Domesday survey, Bradford was part of the parish of Dewsbury and Ilbert de Lacy, who came over with William the Conqueror, was the Norman lord of the manor. It is said that Eldred Beaney restored the church in 1096. This may have been because of fighting and unrest that occurred in the area, as a result of the Conquest.

A Stone Church and Scottish Raiders

A stone church, about half the size of the present nave, was built around 1200. A market charter was granted in 1251 to allow the holding of medieval weekly markets on a Sunday, in order to encourage attendance at worship.

The first mention of the parish of Bradford as distinct from being part of the parish of Dewsbury appears in the register of the Archbishop of York in 1281. Alice de Lacy, widow of Edmund de Lacy, one of the descendants of Ilbert de Lacy, gave a grant to the parish of Bradford that is recorded in the register of the Archbishop Wickwayne.

It is also recorded that the de Lacys endowed the church with 96 acres of land, and the ground adjacent to the church was used not only as a burial ground but also for the holding of markets and fairs.

Around 1327, Scottish raiders burnt down most of this stone church, leaving only the four pillars now standing on the south side, nearest the chancel. Further physical evidence of this church and its fate was unearthed when fire-blackened stones and the foundations of an earlier building were found during the mid-twentieth century extension work.

Fourteenth Century Rebuilding

The rebuilding work, which created the present church, began in the late fourteenth century, having been delayed by war, famine and plague. Early work included two proprietary chapels for the Leventhorpe and Bolling families, and the nave arcades. The rebuilding was largely completed by 1458, with the addition of the tower in 1508, for which it is believed Sir Richard Tempest was largely responsible. The stone came from a nearby quarry, and a steep old cart track leading to this was uncovered when foundations were being laid for the Song Room at the west end in 1951.

Reformation Remnants

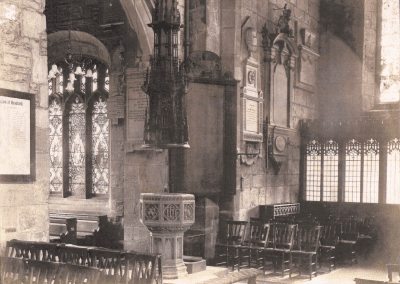

During the period of the Reformation in the sixteenth century, the two chapels were dissolved and the rood screen across the Chancel was destroyed, though the stairs that led up to it remain. Part of the wall of the Leventhorpe Chapel, together with the beautiful carved wooden font cover, also survive as evidence of this period in the building’s history.

Wool and warfare

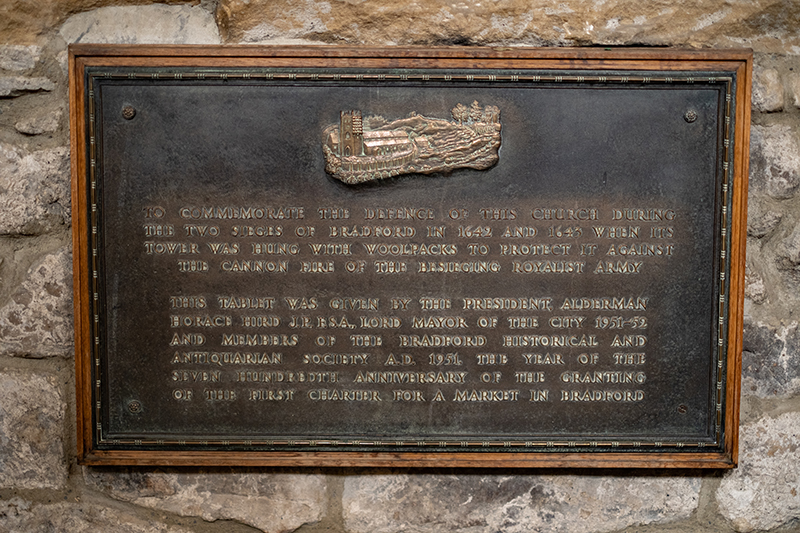

During the Civil War sieges of Bradford in 1642 and 1643, Royalist forces attacked the town, which had fewer than 3,000 inhabitants. In July 1643, after Sir Thomas Fairfax retreated from the battle of Adwalton Moor, the church tower came under threat from Royalist cannon fire and was hung with woolsacks for protection, an event known as the Battle of the Steeple. Cannonballs have since been unearthed at the foot of the tower. The woolsack on the Cathedral coat of arms is a reminder that the church was saved from destruction in this way during the Civil War.

Interesting Additions

The bells- originally only four of them- were first hung around 1666 and the clock was installed not long after this. For a long time, this was the only public clock in Bradford. The original roof was a thatched one, and the churchwardens’ accounts show many entries concerning repairs to the thatched roof. An oak roof was eventually put up in 1724, with the wood coming from Tong Forest.

An Industrial City

During the eighteenth century, at a time of religious revival and as the only Anglican church in this area, Bradford Parish Church congregations were so large, often numbering 3,000, that galleries were installed over the north and south aisles, and across the west and east ends. The walls were whitewashed and a false ceiling put in. The aisle roof level was raised to accommodate the galleries and a triple-decker pulpit was installed half way down the church. From the top level of that pulpit, John Wesley preached in 1788.

In 1810, the Parish of Bradford was said to be 51 square miles, ranging from Ponden, Queensbury and Oakenshaw to Eccleshill. There was a chapel of ease at Haworth.

Nineteenth Century Restoration

By the mid-nineteenth century, a programme of church and chapel building all over the town dispersed the large congregations and the redundant galleries were removed, in a major restoration project. Evidence of this remains in the change of stones at the top of the windows, where the wall stones become regular in size and smooth in texture. The plaster false ceiling was also taken down, so that the beautiful oak roof was visible again.

Only half a century later, another major change was made to the nave, with the addition of transepts, in the late 1890s.

(Left: South transept, right: North transept)

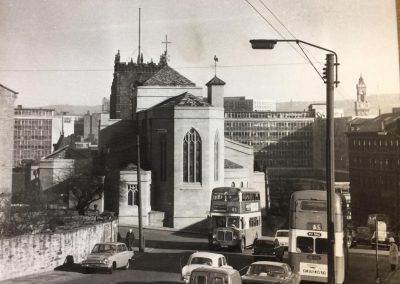

The Birth of a Cathedral

Bradford Parish Church became a Cathedral in 1919, with the Bishop’s Throne- the “Cathedra”, which comes from a Latin word meaning “chair”- given by the people of Ripon diocese, from which the new diocese of Bradford was created. Plans were then made for major extensions to the building, but these were delayed by the outbreak of war.

WW1 Memorial bells

In 1921 the bells, at that time numbering ten and in poor condition, were recast as a memorial to the men of the parish and city who gave their lives in the First World War.

Cathedral Extensions of the 1950s-1960s

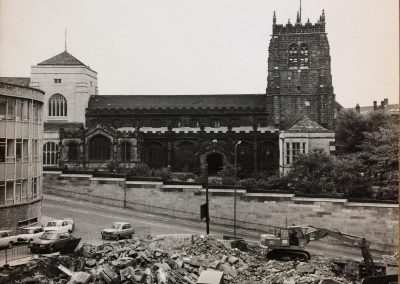

In the early 1950s, approval was given for the designs of Sir Edward Maufe, RA, and over the next decade the east end of the Cathedral was rebuilt and extended and wings for a Song Room and offices were added at the west end. The east end was rededicated in 1963 by Archbishop Coggan. As well as a new Chancel it included a Sacristy, St Aidan’s Chapel, a Chapter House, the Chapel of the Holy Spirit, the Lady Chapel, a Library and Muniments Room, and Ambulatories to the north, east and south.

In the next decade the northern part of the graveyard was landscaped to form a Close, and houses were built for the Provost (now called Dean) and two Residentiary Canons. The Parish Room was altered so that it could be entered from the Close.

Cathedral Extension

The Cathedral pictured on October 1967 with the extension at the front. (Telegraph & Argus)

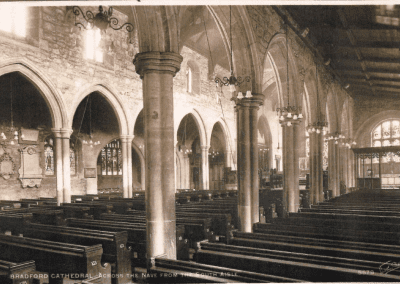

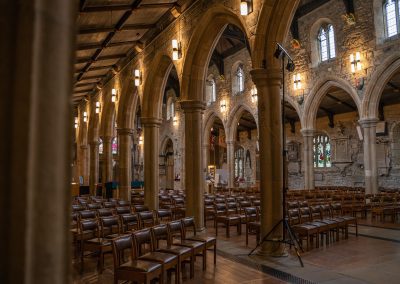

Changes to the Nave

In 1987 the Nave and west end were re-ordered so as to provide the setting and amenities needed for the increasing number of visitors and the many varied occasions when large numbers of people come to the Cathedral. To enable flexibility of use the Victorian pews were replaced by chairs. The nave organ was removed to give more light and space at the west end and new entrances were made through the tower walls to the offices and Song Room.

Eco Cathedral

Bradford Cathedral was the first cathedral in the north of England to receive the prestigious Eco Congregation Award. In 2011 42 solar photo voltaic cells were installed on the South Aisle roof, making it the first cathedral in the country, to generate its own power.

The Cathedral Today

Bradford Cathedral continues to serve its flourishing congregation and to welcome visitors of all faiths and none to this hidden treasure at the heart of a busy, vibrant and growing city. The Parish Room has recently been refurbished and renamed as the de Lacy Centre, providing more room and facilities for groups who wish to meet on this site.

Alongside worship, there are also thriving music and education departments and the Cathedral hosts concerts, visits, festivals and exhibitions, whilst embracing local, civic, cultural and interfaith partnerships.

The ‘de Lacy Centre’: Why is it called that?

Our association with the de Lacy family goes back to Norman times. At the time of the Domesday survey in 1086 Bradford was part of the parish of Dewsbury and Ilbert de Lacy was the Norman lord of the manor. It is likely that Ilbert would have had a chapel on his manor and there may well have been a small wooden or wattle church here during the Norman period.

Alice de Lacy was a local benefactor and a key figure in relation to the Cathedral’s history and its growth during the late thirteenth century and onwards. She was the widow of Edmund de Lacy, a descendant of Ilbert de Lacy.

Looking through documents, records and memorials, we can find many male figures with historical connections to the Cathedral because of their position or actions, but it is quite rare to find a record of a female with a direct link to the Cathedral’s history.

The first mention of the parish of Bradford as distinct from being part of the parish of Dewsbury appears in the register of the Archbishop of York in 1281. Alice de Lacy gave a grant to the parish of Bradford that is recorded in the register of Archbishop Wickwayne. We also know the name of the rector appointed to the job by Alice de Lacy, Robert Tonnington.

It is also recorded that the de Lacys endowed the church with 96 acres of land, and the ground adjacent to the church was used not only as a burial ground but also for the holding of markets and fairs.

As with many women of that time, not a lot is known about Alice de Lacy personally, other than in relation to her husband and children. She was born Alesia di Saluzzo c. 1230 in Savoy, Italy. She was related to Queen Eleanor of Provence, the wife of King Henry 111. She married Edmund de Lacy in May 1247, at Woodstock Palace, Oxfordshire. She died before 1311 and was buried in the Church of the Black Friars, Pontefract.

Alice and Edmund’s son, Henry de Lacy, was a great friend of King Edward 1 and was present at Edward I’s death. He was the most senior of the English earls and remained influential during the early years of the reign of Edward II. He was buried in the old St Paul’s Cathedral and his tomb, along with the Cathedral, was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666.

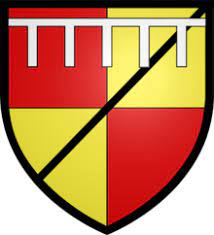

The shield of Henry de Lacy, 1249-1311, (See opposite) can be seen on the wall of the south choir aisle of Westminster Abbey. It is one of a series of shields of individuals and families who were benefactors to the building of Westminster Abbey (from 1245-1272).