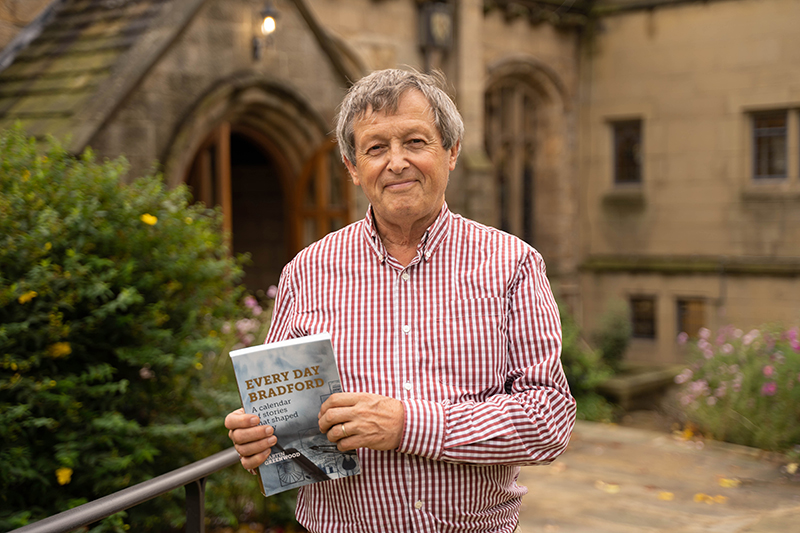

Every Day Bradford – by Martin Greenwood

Published in this year’s lockdown, Every Day Bradford, my history of Bradford, is no conventional narrative. It celebrates each day in the year with a memorable story from 1212 to 2020 and covers a wide range of topics from industry to education, health, culture and religion.

The role of the Anglican Church is one fascinating theme in the book, set against the rise of nonconformism in the nineteenth century. Since the earliest records of Bradford, the parish church, St Peter’s, had of course been its first place of worship. Built in the 14th century, it was in fact the third church on the site and the centre of the small community established around the ‘broad ford’ through which the Bradford Beck flowed. It developed into what is now Bradford’s oldest institution.

However, space only permits a selection of key events (highlighted in bold), where St. Peter’s features in the history of the city, and in one case the history of the country.

Bradford in the Civil War

The importance of St Peter’s Church was recognised in one of the earliest stories in the book on 18 December 1642 when the Parliamentarians won the first Siege of Bradford in the emerging Civil War. The township was Puritan and sympathetic to Oliver Cromwell, and his idea that Parliament, not the King alone, should have the final say in all matters of law. Surrounding areas, however, were generally Royalist.

The Fairfaxes were the leading military commanders for the Parliament in the north – Fernando Lord Fairfax of Denton Park, Otley and his son Sir Thomas Fairfax. Neither side had overall control in the north. The Royalists needed to subdue troublesome towns like Bradford.

In late October Royalists had come to Bradford after establishing a base in Leeds, but were beaten off by the townspeople of Bradford. This led to a new Royalist leader – the Earl of Newcastle in charge of a force of 9,000 men. He turned his attention to Bradford. As the town had no regular Parliamentarian soldiers, he assigned a small force of around 800 men under Sir William Savile to take control of the town.

He positioned his men a few hundred yards on high ground to the north of the centre at Undercliffe, overlooking the parish church, occupied by a few men with muskets. Savile called upon the inhabitants to surrender, but the defending force of around 300 irregulars tenaciously refused. The next day, with defeat likely for the Parliamentarians, the weather intervened with a blizzard and one of the big Royalist cannons exploded, killing several of their soldiers.

The Royalists retreated, but, as they were likely to return, the Parliamentarians reinforced their defences the next day, a Saturday. The plan was to turn the parish church into a fortress. If that worked, Bradford might be saved. They hung large sheets of wool over the steeple and placed the best dozen shots or so around it.

Today, Sunday morning, the Royalists attacked again, expecting the opposition to be at prayer. After an inconclusive exchange of fire, midday reinforcements from Bingley and Halifax gave the Parliamentarians the upper hand and the Royalists were brutally routed in a skirmish that became known as the Battle of the Steeple (the church at the time having a steeple).

The first Siege of Bradford was over, but within six months the second Siege of Bradford after the Battle of Adwalton Moor witnessed the Royalists overturning the Parliamentarian success of six months earlier.

The most prominent 17th century Anglican

A Bradfordian born in the Civil War into one of the place’s most established families became the Archbishop of York in 1691. To this day, John Sharp, educated at Bradford Grammar School, at that time adjoining St Peter’s, remains the most prominent Anglican to have come from Bradford. The high point of his role in the Church of England came on St. George’s Day, 23 April 1702, when he was invited to preach at Queen’s Anne’s coronation, rather than the Archbishop of Canterbury, less favoured by her.

The rise of nonconformism

From the last eighteenth century the growth of the Industrial Revolution led to a sharp expansion in the size of Bradford and with it the rise of non-conformism. Most prominent Bradfordians such as Sir Titus Salt were non-conformists rather than Anglicans, reflecting new trends in religious faith. This was neatly illustrated in the 30 March 1851 Census when for the first and only time the Census contained a separate survey on religious worship, completed by ministers of religion. In Bradford it showed that only 23% of the population that worshipped were Anglican, compared with 68% of non-conformists (eg Methodists, Congregationalists etc) and 9% of Roman Catholics. However, 57% of the official population did not participate in any religion. There were 12 Anglican churches, 41 nonconformist places of worship and just one Roman Catholic church.

The most prominent 19th century Anglican

Most prominent clergymen in 19th century Bradford were nonconformists, such as Jonathan Glyde (Congregationalist) and Benjamin Godwin (Baptist). The one Anglican who can be added to this list is Reverend William Scoresby (1789 -1857), Vicar of St. Peter’s Church and head of the whole parish. He was only in Bradford for seven years from 1839 to 1846, but he was the most energetic and controversial vicar in the century. He also had the most colourful background for such a traditional role, coming to it as an Arctic scientist.

His father was captain of a whaling ship. As a ten-year-old, Scoresby made his first voyage to the Arctic. From 1803 to 1823 he sailed each summer to the Greenland whale fishery. When 21, he became captain himself on one voyage. Stimulated by studies at Edinburgh University, he became passionately interested in scientific research related to such voyages (eg navigation, astronomy), frequently lecturing on this even during his hectic life in Bradford.

He had also developed deep religious convictions and in 1822 decided to enter the church. He studied at Queens College, Cambridge over a ten-year period, taking positions of deacon at Bridlington and chaplain at Liverpool and Exeter. In 1838 he was offered the position of Vicar of Bradford.

Here he identified several problems about his new role. They included the inadequacy of church accommodation, the shortage of clergy, the neglect of education and the general lack of discipline in the parish. He ran into difficulties, explained by an autocratic management style, no doubt acquired during his youthful sailing experiences.

Although he did achieve much, he had the habit of alienating people. For example, he established four day schools after realising that the parish church did not educate any children. However, his argument against over-worked children in mills lost him the support of influential mill-owners.

The issue that caused the greatest problem was the levying of church rates to support the parish, which nonconformists still had to pay. He inherited a history of recent conflict, losing an important poll within his first year, which led to large numbers uniting against him.

On 14 May 1841 he managed to force through the approval of a new rate, despite much vociferous opposition. However, many people refused to pay, including Titus Salt. Eventually, in a test case the High Court deemed the rate illegal.

The new diocese of Bradford

One of the most important dates in the life of Bradford’s parish church was 25 November 1919 when the Diocese of Bradford was created. Historically, Bradford had been part of the Diocese of Ripon. Its rapid growth in the 19th century made this increasingly inappropriate, given that at the start of the 20th century Ripon, 30 miles to the north of Bradford, was still a small rural market town, in contrast with Bradford, now a large industrial city.

Before a new Bishopric could be founded, appropriate funds had been secured. Dividing Ripon Diocese like this still left it one of the largest in the country with the new diocese stretching through the Yorkshire Dales up to Sedbergh. On 8 January 1920 the first Bishop of Bradford was appointed.

Bishop Blunt prompts the abdication crisis

Bishop Blunt, the second and longest-serving Bishop of Bradford, made a speech on 1 December 1936 that inadvertently triggered the crisis leading to the abdication of King Edward VIII.

Speaking at a Bradford Diocesan Conference, he used words, suggesting that the new king who had taken over back in January on King George V’s death had become detached from grace – the spiritual bond uniting God, the monarch and the people. Without this a king could not undergo the rites of coronation.

The day before, the king had given Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin an ultimatum – either Mrs Simpson became his queen or he would abdicate. The king’s relationship with Mrs Simpson, an American divorcee (twice) had been the subject of rumour for months. He was the head of the Church of England, which did not then allow divorced people to remarry in church if their ex-spouses were still alive. Mrs Simpson would be an unsuitable queen.

The bishop’s words may have gone unheeded, had not two Telegraph & Argus reporters been covering this conference. Their report quoted the words verbatim. The reporters agreed that the media might be interested and sent it to the Press Association. The story broke in the national press, which was widely disapproving of the king.

On 10 December the king abdicated to be replaced by his younger brother who became George V1. The day after, he broadcast to the nation about his abdication.

Major extensions to St. Peter’s

Although Bradford was made a diocese in 1919 and overnight St. Peter’s became a cathedral, it took 44 years and four bishops before building extensions were completed to create the feel of a cathedral. They comprised the new Sanctuary, the Lady Chapel and the Chapel of the Holy Spirit. Seen from the western side of the church, the extensions seemed almost to double the length of the building. The focal point of the Sanctuary was an altar, 11 feet long, built in oak.

The long-awaited opening celebrations lasted three days, finishing on 2 November 1963 with a special 3pm choral evensong of thanksgiving for 700 lay representatives of parishes in the diocese, unable to attend the consecration.

Two days earlier, the Archbishop of York, Dr Donald Coggan, who had also been the third Bishop of Bradford from 1956 to 1961, had consecrated the new extension. He said that ‘(it) combined the beauty of the old and the new in wonderful harmony’. A congregation of 1,000 included three Roman Catholic priests from the city, almost certainly the first time when priests appeared officially in the building since the Reformation in the 16th century.

The extensions included the refitting of the East Window, containing valuable stained-glass windows designed by William Morris 100 years earlier. Originally one window, it was now refitted as three separate windows, a feat involving 30,000 pieces of glass.

The architect also had strong Bradford connections. Born in Ilkley, Sir Edward Maufe, whose father Henry Muff was a draper at Brown Muff & Co, married a niece of Sir Titus Salt. After changing his name by deed poll from Muff to Maufe, he became an architect with a national reputation, responsible for the design of Guildford Cathedral. He was present at this week’s consecration.

Some fifty years later and ninety-five years after the Diocese of Bradford was created, Bradford Cathedral rang with the songs of hundreds of worshippers and guests as the diocese celebrated its final anniversary. It was about to be dissolved in a few days’ time on Easter Sunday and merged with Leeds and Wakefield to become the Diocese of West Yorkshire and the Dales, centred on Leeds. The total population for the new diocese would be 2.6 million and include 656 churches, making it the largest diocese in the country.

This means that the Cathedral is now formally the parish church of the city centre, being the only Anglican church within the city’s inner ring road.

Sources:

The Story of Bradford, Alan Hall (2013)

Bradford Remembrancer, Horace Hird (1972)

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (William Scoresby)

Leeds Mercury

Telegraph & Argus

Every Day Bradford by Martin Greenwood, 432 pages, 32 half-page images, available from Waterstones, Salts Mill and almost all online book stores (£18.50 softback, £22.50 hardback, £9.99 Kindle)